How to Make Your Writing Like a Flashlight

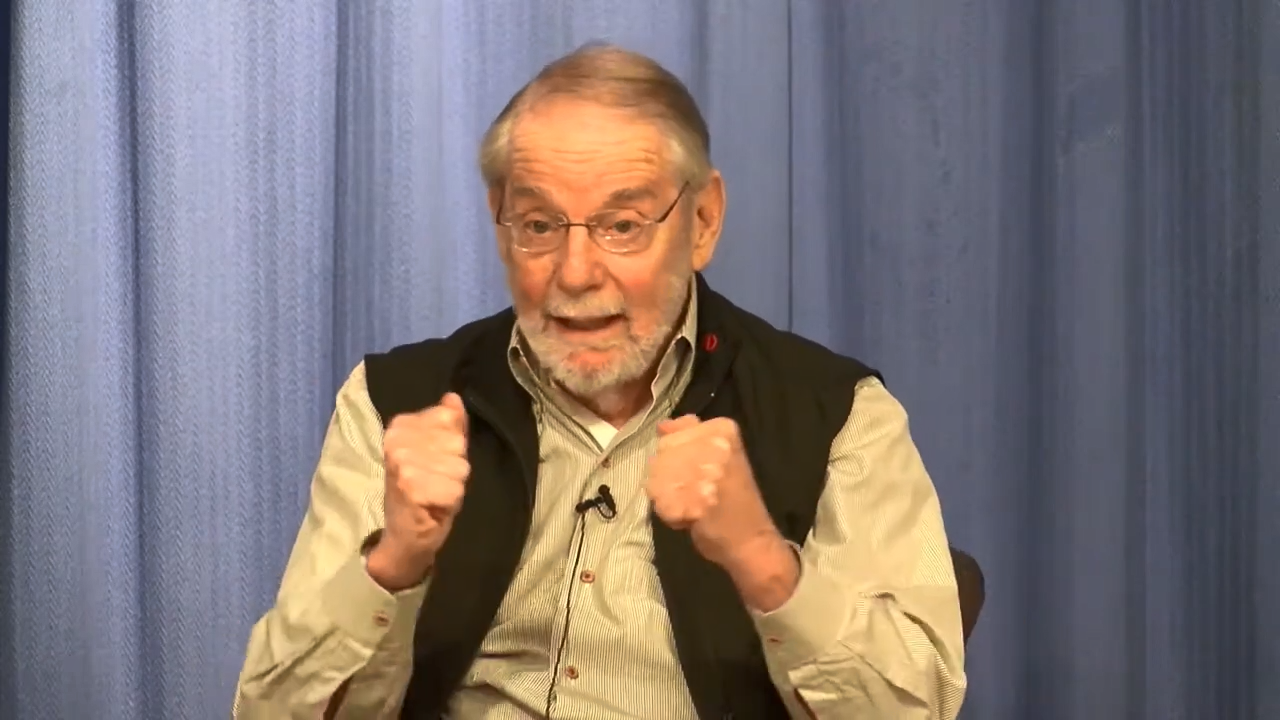

9 Lessons from The New Yorker staff writer John McPhee

John McPhee wrote four drafts of “Assembling California,” his 303-page story about the geology of the Golden State, published more than 30 years ago.

“That four-to-one ratio in writing time—first draft versus the other drafts combined—has for me been consistent in projects of any length, even if the first draft takes only a few days or weeks,” he recalls.

Thus, the title of “Draft No. 4: On the Writing Process,” a collection of essays published in 2017 that I recently stumbled upon on the way to something else.

McPhee, 93, might seem to be an unlikely source of advice for many writers because of his unique career. He joined The New Yorker in 1963 where he turned in stories that were tens of thousands of words long. Considered a pioneer in creative nonfiction, many of those magazine pieces were revised and published as books. He’s written 34 of them.

He’s a meticulous reporter who has tackled a wide range of subjects, but is particularly adept at explaining technical topics such as aeronautical engineering, the environment and geology, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize in 1999.

Yet he’s also taught writing at Princeton University since 1975, and that experience imbues Draft No. 4. He illustrates his points with excerpts from his work so that the reader can see his thinking in action―or writing.

We’ve highlighted just nine of the many lessons the book contains:

1. Write and revise. Most corporate communicators and journalists would love to have the time to write four drafts of anything, a luxury McPhee has enjoyed and appreciates. Yet he would agree that even a second draft can help.

“The essence of the process is revision,” he writes. “The adulating portrait of the perfect writer who never blots a line comes Express Mail from fairyland.”

The value of rewriting is one of McPhee’s many lessons that we too offer during the workshops and one-on-one editing sessions of our Build Better Writers program.

2. Personalize the story. Too often corporate communicators write about policies and procedures. “The solution: Write about people,” we’ve written before.

McPhee began his career writing profiles at Time, which he joined in 1957. Early in his career at The New Yorker, to emphasize the importance of character, he put a piece of paper on a wall with “ABC/D” in large block letters. Each letter would be a person in the story, with “D” the main character.”

“The letters represented the structure of a piece of writing, and when I put them on the wall I had no idea what the theme would be or who might be A or B or C, let alone the denominator D,” he wrote. “They would be real people, certainly, and they would meet in real places, but everything else was initially abstract.”

Such a formula may seem simplistic, but it underscores a key insight: Your story may not have four characters, but it must have at least one.

3. The first sentence. “The lead—like the title—should be a flashlight that shines down into the story,” McPhee writes. “A lead is a promise. It promises that the piece of writing is going to be like this. If it is not going to be so, don’t use the lead.”

Features and news stories will start differently, but the purpose is the same.

“A good lede or opener should give readers a running head start,” we’ve written before.

4. Write the lede. Before writers start work, we recommend a story pitch memo, which has the first draft of a headline, first sentence, as well as graphic and photo ideas. Answer the question: Why should the audience care?

“Often, after you have reviewed your notes many times and thought through your material, it is difficult to frame much of a structure until you write a lead,” McPhee writes. “Writing a successful lead, in other words, can illuminate the structure problem for you and cause you to see the piece whole…. I would go so far as to suggest that you should always write your lead (redoing it and polishing it until you are satisfied that it will serve) before you go at the big pile of raw material and sort it into a structure.”

5. Write the headline. “The title is an integral part of a piece of writing, and one of the most important parts, and ought not to be written by anyone but the writer of what follows the title,” McPhee writes.

Readers prefer headlines that are simple but engaging. No easy task.

6. Write crap. McPhee writes grimly about the anxiety sometimes induced by writing.

Before one project, he laid on a picnic bench in his backyard for two weeks, “fighting fear and panic, because I had no idea where or how to begin a piece of writing,” he writes.

We have a tip for the Pulitzer Prize winner and others who suffer from writer’s block. The CRAP method: Craft Really Awful Prose.

“Free yourself from the bonds of perfection!” my colleague Jim Ylisela has written. “When you write a draft ― even a lousy one ― you are so much closer to the finish line.”

7. Be a better reporter. We often find that “problems in writing stem from holes in the reporting,” as we’ve written before. “We resort to adjectives because we don’t have the details, the color we need to paint a picture.”

In his writing classes, McPhee writes this mantra on the chalkboard, “A Thousand Details Add Up to One Impression.”

“It’s actually a quote from Cary Grant,” McPhee writes. “Its implication is that few (if any) details are individually essential, while the details collectively are absolutely essential. What to include, what to leave out. Those thoughts are with you from the start.”

8. Box them in. As he’s writing and revising, McPhee puts boxes around any word that’s not quite right or could be better.

“While the word inside the box may be perfectly O.K., there is likely to be an even better word for this situation, a word right smack on the button, and why don’t you try to find such a word?” he writes. “If none occurs, don’t linger; keep reading and drawing boxes, and later revisit them one by one.”

We might include this tip in an update to our “Self-Editor Checklist.”

9. Check the definition. Microsoft Word users are accustomed to right-clicking on words to find synonyms, a practice that McPhee would disapprove of.

“I spend a great deal more time looking up words I know than words I have never heard of—at least ninety-nine to one,” McPhee writes. “The dictionary definitions of words you are trying to replace are far more likely to help you out than a scattershot wad from a thesaurus.”

We agree, but Peter Mark Roget might have balked.

We enjoy reading books by writers about writing to see how our tips, tricks and teachings compare with theirs. Why do writers write these books?

“Perhaps writers wax about craft because it’s the easiest part of writing to talk about,” Parul Sehgal, now a staff writer with The New Yorker, wrote in a review of Draft No. 4.

Tom Corfman is a senior consultant with Ragan Consulting Group who began reading The New Yorker in elementary school―for the cartoons.

Contact our client team to learn more about how we can help you with your communications. Follow RCG on LinkedIn and subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.