A Camel’s Genitalia and Other Writing Lessons from Calvin Trillin

7 tips collected from the insights into journalism by the longtime staff writer for The New Yorker

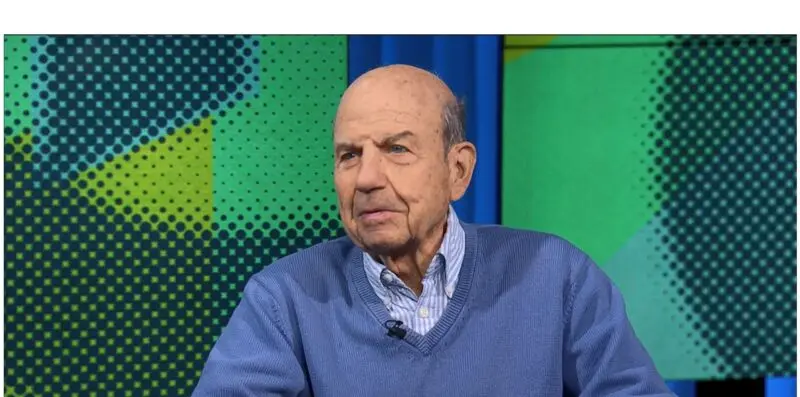

Anyone looking to polish their writing would do well to check in this month with Calvin Trillin, a staff writer for The New Yorker since 1963 and the author of more than 30 books.

Even those satisfied with their skills will enjoy “The Lede: Dispatches from a Life in the Press,” a collection of previously published stories about what Trillin calls “the trade.”

While reading the book in the current era of the hard-pressed news media, readers cannot help but supply their own sense of nostalgia. Yet despite the passage of time, many of Trillin’s insights into reporters, what they do, and how think hold true.

His observations about writing are as fresh as ever. Here’s seven tips gleaned from “The Lede:”

1. Sit down and start writing. “A common complaint then among Time writers who found themselves stuck was ‘this story just won’t write’—as if the story had a will of its own and was using it to resist being shaped into a coherent narrative,” Trillin wrote. “I may have used the phrase from time to time myself.”

The prolific writer doesn’t offer a solution, but we do: Stop worrying about getting the first words right, just get a draft done. Then, rewrite and rearrange.

As Ernest Hemingway said, “The first draft of anything is shit.”

2. No magic trick. This isn’t to say that writing sometimes will always be easy, even if getting a draft on the screen helps. Richard Harris, who died in 1987, worked at The New Yorker for 25 years, starting as a fact-checker and quickly becoming a staff writer.

With empathy Trillin wrote, “He struggled to hit his stride as a writer, and then, when he had, he struggled with every piece he wrote.”

3. “Short, punchy ledes.” When James Thurber was a reporter for the New York Evening Post in the early 1920s, an editor said the lede, or first sentence, to a story was wordy. Thurber rewrote the top of the story this way:

Dead.

That’s what the man was when they found him with a knife in his back at 4 p.m. in front of Riley’s saloon at the corner of 52nd and 12th streets.

Trillin also offers an example by Edna Buchanan of the Miami Herald, who won the Pulitzer Prize for general news reporting in 1985.

The story was about an inebriated customer at a crowded Church’s restaurant who tried to cut in line to order a three-piece box of fried chicken. He was forced to get in line. When he finally reached the counter, he was told the restaurant was out of chicken. That touched off an argument, he slugged the young woman behind the counter and was shot dead by security guard. Buchanan’s lede?

“Gary Robinson died hungry.”

Trillin’s conclusion: “I admire those short, punchy ledes often employed by crime reporters.”

4. “Engage the reader.” Not all the ledes Trillin likes are short. The book takes its title from a 2021 story in which Trillin analyzed a lede from a 2019 story in The Advocate of Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

A veterinarian prescribed antibiotics Monday for a camel that lives behind an Iberville Parish truck stop after a Florida woman told law officers she bit the 600- pound animal’s genitalia after it sat on her when she and her husband entered its enclosure to retrieve their deaf dog.

“If the function of a lede is to engage the reader, this article’s lede seemed to me remarkably effective,” Trillin wrote.

It also starts with the most action, part of the old family recipe for lede writing.

Breaking the rules is an approach we have endorsed.

5. Audition your ledes. Deadlines are deadlines, but it’s nice to have a little time before writing to try out your lede on family, friends, coworkers or even bartenders.

As an example, Trillin cites Murray Kempton, “a palpably erudite columnist who wrote sentences so ornate that they could inspire attempts at team parsing.”

Beat reporters often resented high-profile columnists, but not Kempton, who wrote for Newsday from 1981 until his death in 1997. Trillin tucks in a lesson on writing ledes.

Hundreds of them [beat reporters] had covered stories with him—looking forward to a courtroom recess or a news-conference delay as a time when Murray might trot out a few of the sentences he was auditioning for his lede or might muse on some human characteristic that somehow linked, say, Montaigne and Bessie Smith and Frank Costello.

(Costello was the head of the Luciano crime family. Smith was nicknamed the “Empress of the Blues. Michel de Montaigne was a philosopher and essayist but not a contemporary of Trillin.)

6. Take the leap. “Any writing requires a leap of confidence—you have to convince yourself that somebody is going to be interested in what you put down on the page,” he wrote, “and believing that you know more about the subject than most of your readers do can work wonders for your confidence.”

Persistent, attentive reporting is necessary to uncover vibrant quotes, colorful details and thoughtful analysis that makes writing compelling.

“Reporting and writing are inseparable,” he wrote.

7. Green your stories. In the era before powerful design software, when print stories had to be trimmed it was done with pencil and paper. At Time, it was called “greening,” because of the color of the pencil used to mark the words and passages to be cut.

The instruction to shorten the story came with the number of lines to be eliminated, such as, “Green 12.” Even in the internet age when stories can expand to the farthest reaches of the universe, tightening your writing is still very valuable.

In 2013, Trillin described the benefits with humor: “The greening I did in Time Edit convinced me that just about any piece I write could be improved if, when it was supposedly ready to hand in, I looked in the mirror and said sternly to myself ‘Green fourteen’ or ‘Green eight.’ And one of these days I’m going to begin doing that.”

Writers who believe these are helpful should be mindful of a Trillin admonition not included in the book: “Every good idea sooner or later degenerates into hard work.”

Tom Corfman, who greens all his stories, is a senior consultant with Ragan Consulting Group, where he leads the Build Better Writers programs.

Contact our client team to learn more about how we can help you with your communications. Follow RCG on LinkedIn and subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.