How to Edit Blockbuster Stories

Starling Lawrence, who died last month, leaves behind some tips that are useful to corporate communication managers

Corporate communications managers who want to make their writers better would do well to study the approach of the editor of blockbusters such as “The Perfect Storm” and “Liar’s Poker.”

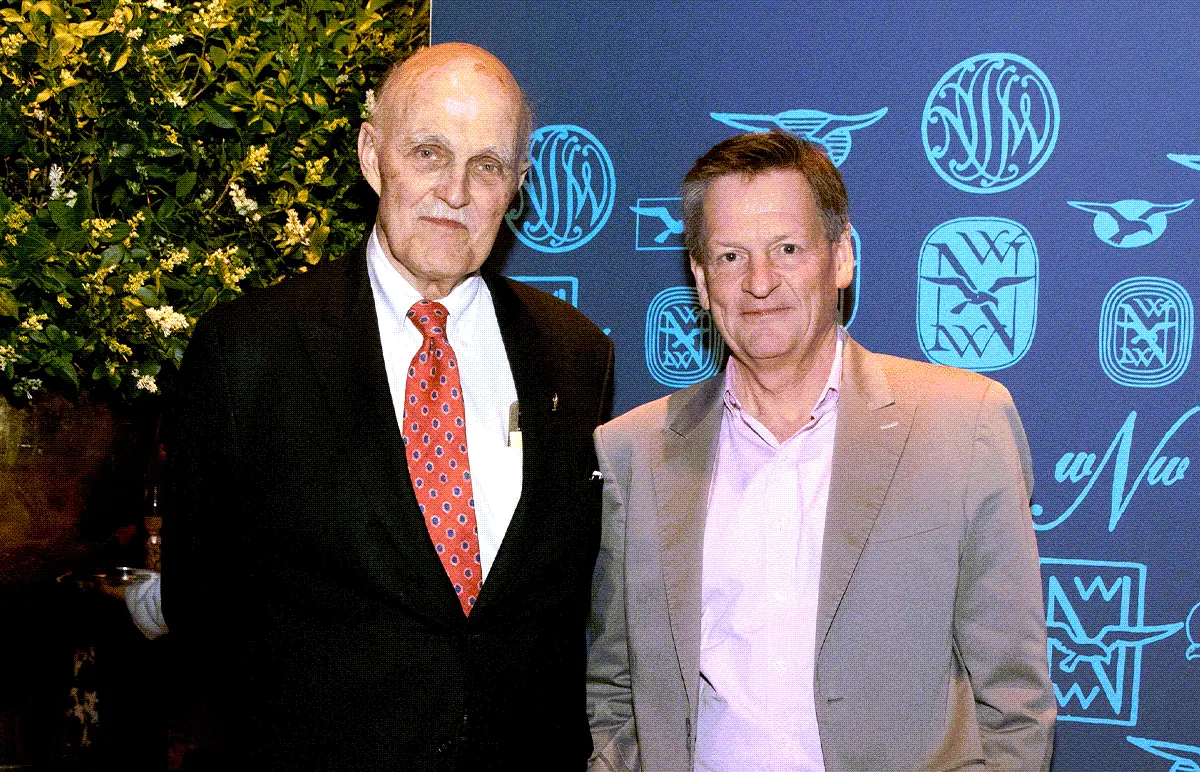

Starling Lawrence was the longtime editor-in-chief of W.W. Norton & Co., where he published Sebastian Junger’s account of the final trip of a Gloucester, Massachusetts fishing boat, and Michael Lewis’ semi-autobiographical story about the Wall Street bond market in the late 1980s.

Lawrence published scores of best sellers, including bring to the U.S. an obscure series of sea novels by an English writer named Patrick O’Brian, starting with “Master and Commander,” which was adapted into a movie starring Russell Crowe.

Despite the high-powered world in which Lawrence worked, he serves as a model for comms managers, for whom editing is a key part of their job.

His death last month at age 82 prompts us to consider why he did his job so well. We asked the same question after the death in 2022 of John Bennet of The New Yorker and Robert Gottlieb in 2023, a prominent book editor and also the top editor of the magazine.

What sparks our interest is a tribute this month by David Ignatius, a foreign affairs columnist for The Washington Post who’s written a dozen spy novels, the last seven edited by Lawrence.

Lawrence — his friends called him Star — joined Norton in 1969 as an assistant editor. Twenty years later, he was named executive editor of the trade department, which publishes general-interest books. He was promoted to editor in chief in 1993 and vice chairman in 2000. He stepped down from those roles in 2011 to focus on editing.

We have six takeaways from Lawrence’s approach to editing.

1. What’s this about? Every story should be about one thing. There may be other things in it, but there should be one dominant theme. Sometimes, that one thing is hard to spot.

Lawrence had a rare ability to spot a story in material that other editors might miss. He credited that knack to his early career as an assistant editor, reading unsolicited manuscripts from what was called the “slush pile.”

“The odds on finding something publishable there were notoriously low, almost infinitesimal, but the work taught me an important lesson about patience and paying attention to the job, no matter what it is,” Lawrence said, according to Publisher’s Weekly.

In addition to the diligence that Lawrence described, finding the story requires the patience to read the story to the end before making changes. Often, the news is at the conclusion.

After you’ve finished, take a step back. Give the story a fresh look.

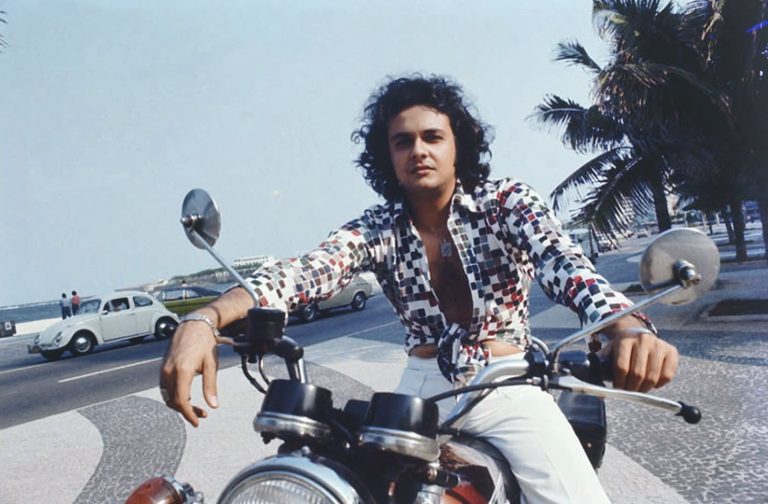

2. Ask questions. In 2024, Lewis recalled meeting Lawrence for the first time to discuss his proposal for his first book, “Liar’s Poker.”

Lewis was a 26-year-old investment banker with little writing experience. He was working with an agent but had received no offers after meeting with several editors.

“That book proposal looked nothing at all like the book that came out,” Lewis said. “It was a dull book about the history of Wall Street, and I was barely in it. When he started working with me, it became something completely different.”

A writer may have a story, but it’s not always the one the writer has in mind. Even if the assignment isn’t tens of thousands of words long, a conversation before reporting starts is invaluable.

The book, “Coaching Writers,” by writing coaches Roy Peter Clark and Don Fry, offers helpful tips for these conversations.

3. Don’t be bored. Comms team are often called to write the same story every week, month or year. It can feel boring. If a writer is bored, the audience will be bored too.

At a writing class at Princeton University, Lawrence was asked how he helped address the narrative structure of Junger’s “The Perfect Storm,” which weaves together several stories about a 1991 hurricane.

“Structure, shmucksher, what I care about is obsession in the author,” he said. “Junger was completely obsessed.”

A writer doesn’t have to be obsessed but must be interested. To spark that interest, sometimes editor and writer must engage in a little brainstorming.

If a writer is psyched about the story, other problems with the text can be fixed.

4. Get a draft done. Lawrence wrote three novels and a collection of short stories. In explaining how his work as an editor influenced his work as a writer, he touched on an obstacle that many writers face: the first draft.

“I don’t really think that skills acquired or exercised in my day job have been very helpful in writing fiction,” he told The Daily Beast in 2013. “In fact, the opposite may be true, because thinking like an editor — worrying about problems before they exist — may make it too hard to get anything down on paper in the first place.”

For an editor, helping a writer write that first draft sometimes means talking out those structural problems. Other times, words of encouragement and praise can work.

Or even frank advice, like that offered by Kevin Costner to Tim Robbins in “Bull Durham.”

“Don’t think. It can only hurt the ball club.”

Sometimes, writers need to be told, “Don’t think, just write.”

5. Keep it tight. Lawrence relentlessly eliminated extraneous words, clichés and tired phrases, according to Ignatius, who describes Lawrence’s line editing in detail.

“Beware of the Obvious!” Lawrence wrote in large letters on the first draft of Ignatius’ novel, “Body of Lies,” published in 2006. “I think it helps to ask whether you are giving the reader information he doesn’t have or can’t figure out himself. And if it is a description of some sort the question should be: Is this original or interesting enough to warrant inclusion? Sometimes cutting beats revising.”

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s precept, “Less is more,” applies to writing as much as architecture.

6. But don’t do this. Lawrence could be quite harsh on drafts.

“His editing, in precise, finely written pencil, was bracing and occasionally lacerating — but almost always right,” Ignatius told The New York Times.

In his tribute to Lawrence, Ignatius said Lawrence’s comments in the margins included: “Ugh.” “Ick.” “Try Again.” “Let’s not.” “No, no, no, no. no, no! If you saw this in a movie you’d get up and walk out.”

And those were “among the milder ones,” Ignatius joked.

Lawrence edited “The Well-Trained Mind,” a best-seller published in 1999 and co-authored by Susan Wise Bauer.

After his death, she wrote on x.com: “I have Star’s acerbic, unsparing, often unkind, and unerringly *right* editorial voice in my head every time I open a manuscript.”

Despite his blunt approach, Lawrence’s writers appreciated his help, but we don’t recommend his manner.

Lawrence wrote for more than a decade before submitting any of his work for publication. When asked to explain the delay, he responded with what he called his motto.

“Nothing in haste.”

It’s good advice when starting to edit every story.

Tom Corfman learned to edit by being edited by talented editors, including a co-founder and senior partner of Ragan Consulting Group. Tom is a senior consultant with RCG, where he directs the Build Better Writers Program. Email Tom to schedule a free, 30-minute conversation.

Follow RCG on LinkedIn and subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.