Four Random Communication Tips that Demand to Be Told

Ideas for organizational communicators, from showing enjoyment to structuring stories

Luigi Pirandello’s absurdist play, “Six Characters in Search of an Author,” is about fictional characters abandoned by their playwright who demand that their stories be told.

This story is about four random communication tips that demand to be told.

My aim is more modest than the accomplishments of Pirandello, who won a Nobel Prize in 1934 and influenced generations of writers, from Samuel Beckett to Edward Albee.

My hope is to provide a little help to internal communications and public relations pros. Here are tips on enjoying communications, getting employees to speak up and structuring stories.

Show enjoyment

In September 2022, Northwestern University graduate students set up a table during a student fair with a sign saying they were conducting market research for a local bakery.

Visitors to the table were asked to choose between two hand-made brownies. The brownies were identical but described by different handwritten signs from the head pastry chef.

One sign said, “I really enjoyed making this version.” The other sign: “It’s a very popular item.”

More than 300 people stopped by. Most chose the brownie with the sign that expressed enjoyment instead of the sign that conveyed popularity.

The grad students weren’t conducting market research. They were studying perceptions of value under the direction of a research team that included Jacob Teeny, a professor with Northwestern University’s Kellogg Graduate School of Management.

“Intrinsic value often comes from enjoyment,” Jacob Teeny told Kellogg’s news site.

Tip #1: Don’t let yourself be bored by your own content. If you’re bored, everyone else will be, too. When you’re interested, there’s a good chance the audience will follow.

Two-way street

As communicators, we spend a lot of time and energy on what we’re telling employees and how we’re telling them. We forget that communication should be a two-way street.

Listening helps lift employee engagement with the work and reduces turnover. It also can prevent big problems.

“The root cause of many crises can be traced back to environments in which employees felt unable, or unwilling, to voice their concerns,” management experts Celia Moore and Kate Coombs wrote last month in the MIT Sloan Management Review.

There are many ways to obtain employee feedback, but managers at all levels of an organization have a crucial role. Yet they’re often poorly trained in internal communications in general and seldom prepared at all in the specific skill of listening.

Saying, “My door is always open,” isn’t enough to persuade employees to speak up. Moore and Coombs, who are with the Centre for Responsible Leadership at Imperial College Business School in London, have five tips to coax workers to open up:

- Ask better questions.

- Acknowledge challenges as legitimate.

- Keep meetings interactive and friendly.

- Give decisions time.

- Create accountability.

They flesh out the tips in their article, making it worthwhile reading.

Tip #2: Review your manager communications tips sheets and toolkits to make sure they include suggestions on soliciting employees’ opinions.

What’s it about?

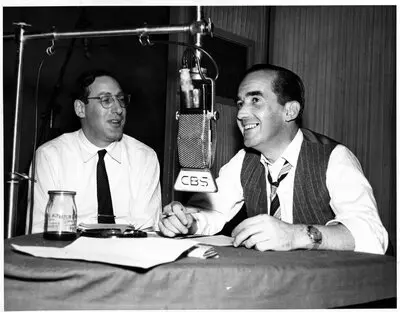

“Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee” offers many tips on writing. In one conversation, Jerry Seinfeld and cocreator Larry David agreed the pilot episode of “Seinfeld” wasn’t very good.

It had “just the barest thread of a story,” David said, which prompted this exchange:

Seinfeld: Right, you need a bigger thing. And then the smaller things live underneath it.

David: Absolutely. But in the end, they combine with the bigger thing. They’re attached in a way.

Turns out, there’s scientific support for that.

“The human brain can only keep a limited amount of information in mind at any given time,” psychologist Charan Ranganath wrote in the Harvard Business Review. The brain’s working memory may hold only three or four pieces of information, he added.

“To get around working memory capacity limits, we can use, ‘chunking’in which we explicitly tie together the points that we want to convey under the umbrella of a central idea,” he wrote. “With this approach, your listener can stitch the pieces together in a meaningful way and build a rich memory for that material.”

We don’t like the “chunks” label, but we agree.

TIP #3: Every story should be about one thing. “Whatever that one thing is, make sure it appears somewhere near the top of the story,” is what we say.

There are exceptions, like this story.

The platter

Trader Vic’s was a Polynesian-themed restaurant in downtown Chicago, one of the earliest locations of a California chain that made Tiki bars popular in the 1950s and ’60s. The Chicago location opened in 1957 in the basement of the historic Palmer House hotel. It closed in 2005 although the chain is still around.

The restaurant was a mishmash of cultures, as I recall. The décor aped a Hawaiian village, with fishnets and Tiki masks on the walls. The founder invented the Mai Tai, one of several cocktails fueled by Caribbean rum. The drinks were often garnished with slices of pineapple or orange and an umbrella.

The menu was mostly Chinese, at a time when such cuisine was a novelty. One popular item was the pupu platter, an assortment of appetizers such as egg rolls, crab Rangoon, fried shrimp and barbecued ribs.

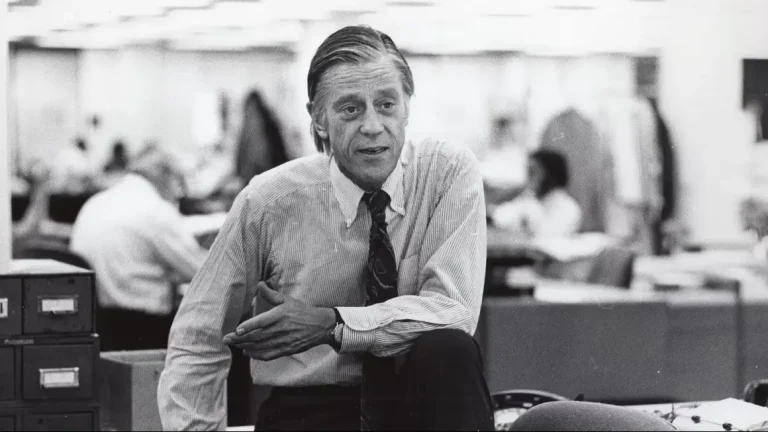

Flash forward to Crain’s Chicago Business, where I was a reporter and an assistant managing editor from 2006 to 2016. There’s a saying in newsrooms, “Twice is a coincidence. Three times is a trend.”

Sometimes we would nail down three unrelated news items that weren’t part of a trend. The only thing they had in common was they came from the same beat. None of the items were newsworthy enough to merit a story on its own, but combined they made interesting reading.

We’d patch ’em together and call it a pupu platter.

TIP #4: Don’t let your format get in the way of a good story. Work with what you got.

Back to Pirandello

The plot of Six Characters, which premiered in 1921, is surreal. Yet there’s a moment that reflects the reality of organizational comms teams.

Act One begins as actors, who are given generic names such as Leading Man and The Director gather onstage to rehearse one of Pirandello’s plays, “Mixing it Up.” The rehearsal is quickly interrupted by a family of unfinished characters, with generic names such as The Mother. They are part of a dropped project.

The Father says they “have come in search of an author” who will write a play about them. That demand sets off a conflict that lasts the entire play between the ‘’actors’’ and “characters” who both claim to be “real.”

Communicators’ carefully planned days are often upended by last-minute requests from inside the organization or crises from out. They can identify with the exasperation of The Director, who has the last line in the play.

“I’ve lost a whole day over these people, a whole day!”

Don’t wait for Godot or for getting our help, says Tom Corfman, a senior consultant with Ragan Consulting Group. Ask us about our Build Better Writers program.