The Wurst Response: Listeria hits Boar’s Head

5 steps the company should take to rebuild its reputation

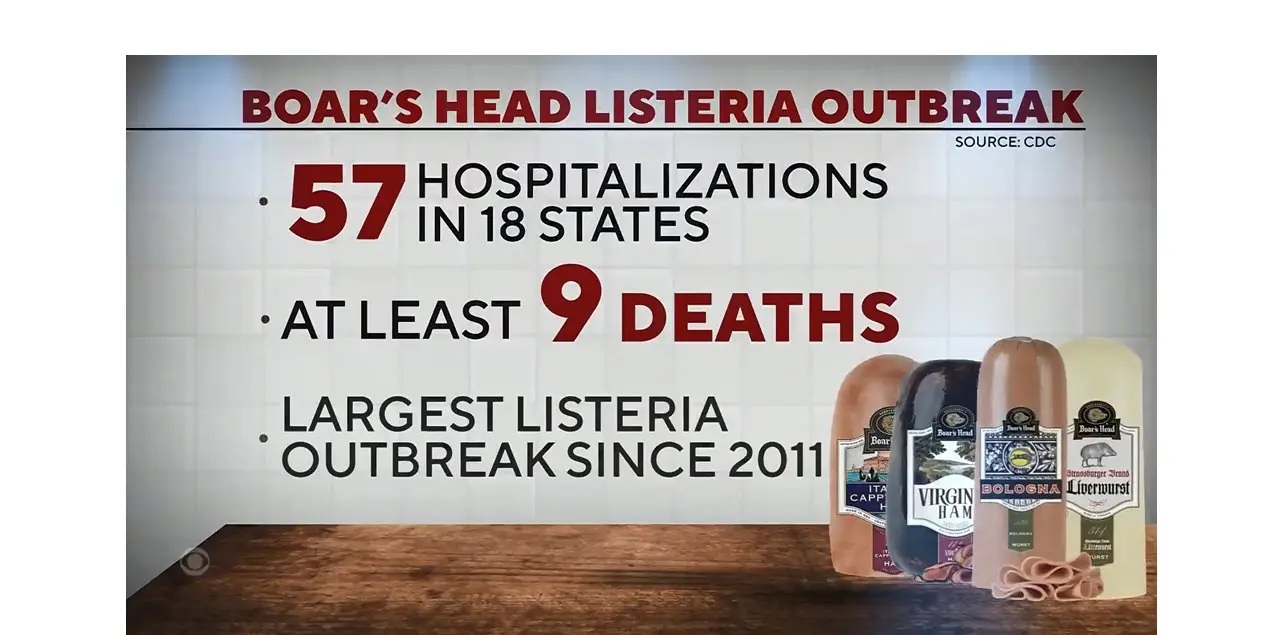

Deli meat maker Boar’s Head risks crippling its brand by continuing a closed-mouth approach to a deadly bacteria infection tied to at least 10 deaths in nine states.

The privately held company faces multiple lawsuits, escalating scrutiny by safety regulators, an emerging federal criminal investigation and possible Congressional hearings.

It’s easy to criticize this crisis communication (or noncommunication) strategy. But it’s time to start repairing the reputation of the company, with estimated annual revenue of $1.3 billion.

On the back of an envelope, we wrote down the ingredients of such a comeback. But first, let’s review how the Sarasota, Florida-based company got itself into this jam.

As listeria began to spread, the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture notified Boar’s Head Provisions on July 25, 2024, that the bacteria had been found in one of its products on a store shelf in Baltimore. The company immediately recalled its Strassburger Brand Liverwurst and nine other products made at a plant in a tiny Virginia town near the border with North Carolina. Five days later, the recall was expanded to 71 products, more than 7 million pounds.

As nearly 60 people were sent to hospitals and the number of deaths mounted, the company said as little as possible. Boar’s Head made three significant updates to its recall web page between Aug. 15 and Sept. 13, according to web.archive.org, then announced it was indefinitely shutting down the plant in Jarratt, Virginia. For example:

- When the USDA announced the recall on July 25, the company said: “The health and safety of our customers is our top priority. As soon as a Listeria adulteration was confirmed in our Strassburger Brand Liverwurst, we immediately and voluntarily recalled the product.” It said it recalled additional products “out of an abundance of caution.”

- On Sept. 13, the company said: “We regret and deeply apologize for the recent Listeria monocytogenes contamination in our liverwurst product. We understand the gravity of this situation and the profound impact it has had on affected families.”

Boar’s Head has refused to answer reporters’ questions. No chairperson or CEO has come forward to publicly take charge.

The brand is especially important to Boar’s Head, which has long portrayed itself as selling high-quality products at premium prices. Rebuilding consumers’ trust in the safety of that brand will require an abrupt change in its comms strategy. Here are five steps the company should consider to mount its comeback:

1. Stop digging. When Boar’s Head shut down the Jarratt plant, about 600 people reportedly lost their jobs, slightly fewer people than the town’s population of 637.

The closure, which affected 500 union workers, created the appearance of an unsympathetic company blaming its employees for its woes.

“Everyone agrees this unprecedented tragedy was not the fault of the workforce,” the United Food and Commercial Workers local said in a statement. Lost in the nationwide coverage was the local’s praise for the company’s handling of the decision.

When making business decisions in a crisis, corporate leaders often don’t consider damage to the company’s reputation, a factor that can be difficult to put a dollar value on.

“If you find yourself in a hole, stop digging,” Will Rogers said.

2. Put a face on the company other than a wild pig. When a crisis hits a company, “the CEO or owners typically get in front of the news and try to instill a sense of calm,” Chloe Sorvino wrote for Forbes.

Boar’s Head did not employ that standard crisis operating procedure, possibly because the two families that control the company have been in court fighting over ownership for decades.

“The warring families who founded Boar’s Head seem more concerned about a series of petty legal battles over the billion-dollar brand,” Sorvino wrote.

In a possible sign of tension at Boar’s Head, a spokesperson even declined to tell Forbes who the CEO is.

3. Come clean. The company needs to start answering reporters’ questions. It’s an opportunity to live up to its tagline from the 1980s: “Pure baloney, not phony baloney.”

When the company stonewalled, reporters sent open records requests to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which released inspection records in late August and again in September, a few days before the plant was closed.

The records paint an ugly picture.

Was it hard to predict that the government would disclose those reports under the federal Freedom of Information Act? Boar’s Head missed an opportunity to try to shape the coverage by voluntarily releasing those documents.

Because of the decision to close the plant, current and former employees may have felt freer to talk to reporters, helping feed several stories about conditions in the plant, such as an investigation by The Washington Post. The company did not respond to the questions from the Post or other outlets, creating an uncontradicted narrative.

The story isn’t confined to one facility. Boar’s Head’s other plants in Michigan, Arkansas and Indiana are part of a “law enforcement” investigation, CBS News reported on Sept. 26, citing a Dept. of Agriculture letter.

4. Get on Social Media. In late July, a Facebook user said it was “very concerning and disappointing” that Boar’s Head didn’t have a link to its recall site at the top of its account.

The company fixed that and has posted three bland messages since then, such as, “You have our promise that we will work tirelessly to regain your trust,” on Sept. 13, the day the plant closing was announced.

It’s the same on Instagram.

On x.com, Boar’s Head has included the recall page, but the last post was on May 13. You wouldn’t know there was a problem on its TikTok account.

In a crisis, a company should increase the volume and frequency of its messages on social media, which is where its customers are.

“In the social media age, silence is deafening,” as we’ve said before.

5. Tell a different story. While answering reporters’ questions, a company can start telling its own story. But not until then because reporters are unlikely to go away.

How do you know when a crisis is over? Reporters will tell you when they stop asking questions.

Boar’s Head has a different story to tell. On the day it announced the closing of the plant, it said it had formed a food-safety council. Some members were already advising the company.

Earlier this month, it said one committee member would become Boar’s Head’s interim chief food safety advisor. Frank Yiannas has worked as a food safety executive for Walt Disney’s resorts and Walmart.

Reporters would be keenly interested in the work of Yiannas and the committee to clean up this mess. But Boar’s Head’s owners must be ready to disclose the problems he uncovers as well as any planned safety changes.

‘Secretive food empire’

On several occasions, the family has considered selling the company, most recently in 2020, The Wall Street Journal reported this month.

Even if Boar’s Head is out of the media meatgrinder, the damage to its brand will show up in declining sales, making the company less valuable to potential buyers.

Boar’s Head’s owners not only refuse to share information outside the company, they’re also tight-lipped within the company. Only family and a few top executives receive basic financial information.

Such a corporate culture discourages other senior leaders from speaking out. And that’s when companies get in real trouble.

Tom Corfman, a senior consultant with Ragan Consulting Group, likes good cold cuts as much as anybody. But he hates when a company misses an opportunity to tell its story, especially during a crisis.

Contact our client team to learn more about how we can help you with your communications. Follow RCG on LinkedIn and subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.