How to Write a Good Ending

The beginning should draw readers into your story. The ending should keep them thinking about it.

We spend a lot of time talking about how to write a good beginning, or lede.

And for good reason. If you don’t pull people in with that first sentence, they’re unlikely to get very far, much less to the end.

How you close your story is just as important. In his essay “Draft No. 4,” famed writer John McPhee tells us to “Start strong, finish strong.” A strong lede, he writes, “should be a flashlight that shines down into the story.” Endings serve to keep the story resonating in a reader’s mind.

Your lede and your ending are always talking to each other, McPhee tells us. “This dialogue helps you to make decisions about the middle pieces.”

So, let’s start with this question: When readers get to the end of your story, how do you want them to feel? Warm and fuzzy? Inspired? Spurred to action?

It all depends on your story’s intent.

There was a time when endings didn’t matter. In the days of “hot type” newspaper production, writers were instructed to use the inverted pyramid so that anyone, including the guys who prepped the copy for the printing press, could chop off the bottom with no need for news judgment, to make the story fit.

Today, stories don’t have to be sliced, especially online. They can run forever, though we don’t recommend that.

And the inverted pyramid has made a comeback, encouraging writers to tell us everything we need to know up front, often in the form of bulleted summaries, á la Axios HQ’s Smart Brevity or The Wall Street Journal’s “Quick Summary.”

We understand that readers are impatient and distracted, so this method makes sense, but only some of the time, as my colleague Tom Corfman has written.

Many stories still work best with a compelling lede that draws us in, a solid middle that takes us on a journey and a gratifying conclusion that leaves us satisfied — or wanting more.

Here are five tips for crafting the ideal off-ramp for your story, with a few examples from some of our favorite brand journalists.

1. Give someone the last word. The quote ending is “a reflex action,” writing coach Chip Scanlan wrote in his essay, “Putting Endings First,” on the Poynter website. Quotes are overused and border on cliché, but they also work, which is probably why so many writers on deadline turn to them for an ending. It’s a way to conclude the story with what matters most.

Jenna Hardie, writing for BOK Financial’s The Statement, alerts readers to changes in their 401(k) accounts for 2026. She takes them through the options for employee savings plans and concludes by emphasizing one tip from BOK expert Brandy Marion:

“Even if you’re not maximizing your contributions, if your employer offers to match a percentage, you should contribute enough to earn the match,” she said. “By not taking advantage of this benefit, you are missing out on ‘free money.’”

2. Leave them something to chew on. Some stories tackle a problem and show how it was solved. That may prompt your readers to consider how they can take on similar issues because you’ve shown them the way, perhaps by linking them to a to-do list or an FAQ page.

Other stories may dissect a problem by offering different points of view and providing readers with the information they need to form an opinion.

For example, I remember a hospital system that published essays from two of its doctors recommending when women should begin regular mammograms. The piece concluded with tips on how women should decide, based on family history, genetics and other factors.

3. Bring us back to the top. Some stories use a main character as a hero confronting a problem or a challenge and trying to overcome it. The middle of the story may be more focused on the details of the solution, but a good way to wrap up is to bring back our hero and share a few final insights (often in the form of a quote).

Cory Phare used this technique in his Dec. 8, 2025, story, “Diagnosed with terminal cancer, Nursing grad overcomes the odds,” published on RED, the brand journalism site of Metropolitan State University of Denver.

It’s the story of Jimena Malta Zuniga, who was diagnosed with terminal cancer as she began her nursing studies and today, five years later, is graduating with her degree. Zuniga’s story is an inspiring one, and it concludes in her own words:

“Challenges do not define our story, we do.”

This is also an example of ending a story with strong quote.

4. Remind us of what we need to do. Some stories urge us to sign up, sign off, join, or take some other action. But reminding us at the end doesn’t mean holding off at the beginning. Hard news stories should open with a strong lede that conveys urgency and end with a reminder, along with a few more details.

Blue Sky News, published by Pittsburgh International Airport, covers a lot of breaking news, like this story: “Starting next year, travelers who still do not have a REAL ID or other acceptable identification will need to pay more in order to fly.”

Evan Dougherty’s story reports that the Transportation Security Administration will start charging travelers who haven’t signed up for a REAL ID and explains the policy. At the end, it gives readers some help by linking them to the TSA’s Real ID page, telling them how to text “Ask TSA” or post questions on the agency’s social media platforms.

5. What does the future hold? What’s next? Some stories describe an event or a set of circumstances that must be resolved. Even the narrative arc, with its emphasis on the climax of the story, requires some resolution of how the events you’ve described, good or bad, change the story going forward.

Kim Polacek, national media manager for the Moffitt Cancer Center, writes about cancer research on the center’s Endeavor news site. Her Dec. 8 story, “New Treatment Approach Could Redefine Standard Chemotherapy for Acute Myeloid Leukemia,” talks about a promising, less aggressive approach to treatment. She ends her story with a look down the road:

“Researchers plan to continue monitoring trial participants over time to assess durability of response and long-term survival. If confirmed, these findings could reshape expectations for how newly diagnosed leukemia is treated.”

One last thing

Endings should not be throwaways or afterthoughts. One good way to get organized is to write the ending first so you know where your story is going.

In his essay, Chip Scanlan quotes Bruce DeSilva, a crime novelist who was then with The Associated Press, who offered this advice at a Poynter Institute conference. At a minimum, DeSilva said, your ending must do three things:

1. Tell the reader the story is over.

2. Nail the central point of the story to the reader’s mind.

3. Resonate.

“You should hear it echoing in your head when you put the paper down, when you turn the page. It shouldn’t just end and have a central point,” DeSilva said. “It should stay with you and make you think a little bit.”

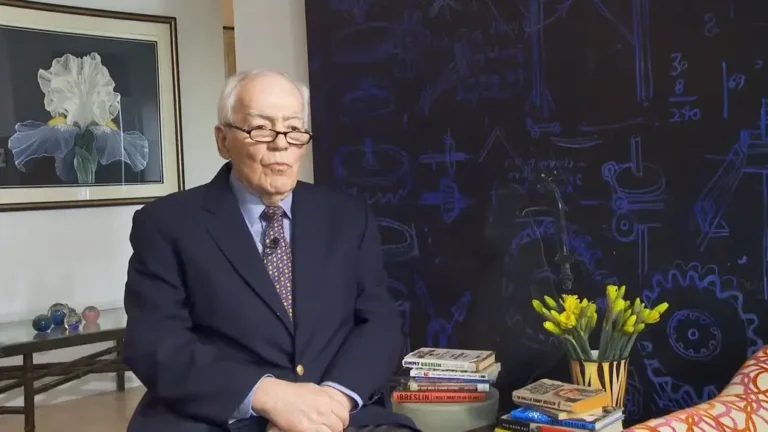

Jim Ylisela loves great endings in literature, including this one from “Charlotte’s Web,” by E.B. White: “It is not often that someone comes along who is a true friend and a good writer. Charlotte was both.”

Jim and his pal Tom Corfman can help you fashion good beginnings, middles and ends in our Build Better Writers program. Email Tom to set up a free call to learn more.

Follow RCG on LinkedIn and subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.