Trump trashes Tylenol. Where’s the company’s CEO?

Kenvue’s boss has kept his head down, raising questions about when executives should speak up in a crisis

The head of the maker of Tylenol kept a low profile after President Donald Trump, defying medical experts, in late September urged expecting mothers not to take the widely used painkiller.

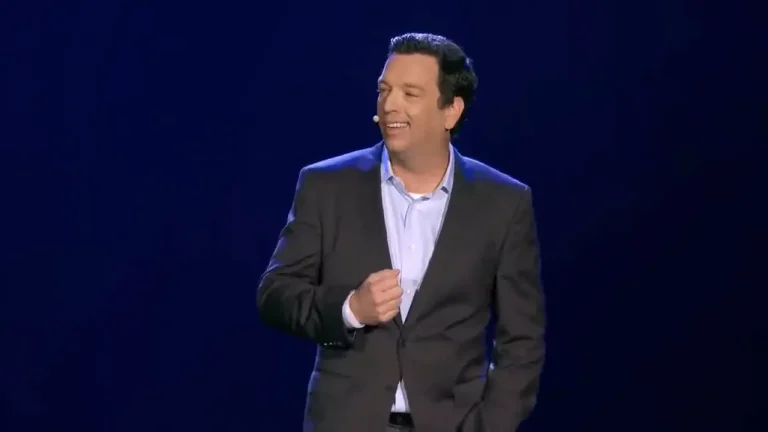

Kirk Perry, who was hired as interim CEO of Kenvue on July 14, 2025, made only one public comment — a LinkedIn post on Oct. 1, nearly a month after the controversy began. He didn’t appear on CNBC, a regular stop for chief executives wanting to reach investors, or morning network news programs, a way to reach worried mothers and mothers-to-be.

Meanwhile, Kenvue’s communications team made the case for Tylenol’s safety in statements to the media, on social media and on its website. But those messages don’t convey the authority and emotion of the person in charge.

The episode gives us an opportunity to consider when a chief executive should become the public spokesperson of a company in crisis. Our aim is not to settle the controversy over Tylenol, although the scientific evidence establishes its safety. And we don’t know enough about the facts to second-guess the communications strategy of Kenvue, which is working with a crisis comms firm.

Allegations that acetaminophen, Tylenol’s main ingredient, causes autism have circulated for some time. Then on Sept. 5, The Wall Street Journal reported that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration was preparing a report suggesting a link between the widely used painkiller and a neurological developmental disorder.

On the day of the Journal story, Kenvue saw its stock price fall more than 30%, to $14.15 a share, from $20.54 on Sept. 4.

President Trump flatly urged expecting mothers to not take the drug at a Sept. 22 press conference with Robert F. Kennedy Jr., secretary of Health and Human Services.

“Taking Tylenol is not good,” Trump declared at the conference where the FDA released its more nuanced report.

Perry kept a low profile despite the threat to a product that accounts for estimated annual sales of $1 billion, according to investment information site Morningstar.

His only public comment came on Oct. 1, nearly a month after news media coverage began. He posted to his LinkedIn account a Sept. 26 memo to employees.

“Acetaminophen is the safest pain reliever option for pregnant women as needed throughout their entire pregnancy,” the memo said. “I firmly believe that moments like these are when you see true character and I’ve been incredibly proud of how each of you has shown up.”

Crash course

Perry had been interim CEO for just 52 days when the Journal published its story. Perhaps he could identify with A.G. Lafley’s start to his nine-year run as CEO of Procter & Gamble in June 2000.

P&G’s stock price had already plunged since March 2000 and fell another 11% during the week after Lafley’s hiring.

“A number of factors had contributed to the mess we were in,” he wrote in the Harvard Business Review in 2009, including an overly aggressive business transformation and internal dissension. “But our biggest problem in the summer of 2000 was not the loss of $85 billion in market capitalization,” he wrote. “It was a crisis of confidence.”

In one way, Perry didn’t share Lafley’s experience.

“At 6:00 PM on my first day as CEO,” Lafley wrote, “I stood in a TV studio, a deer in the headlights, being grilled about what had gone wrong and how we were going to fix it. Everyone was looking to me for answers, but the truth was that I did not yet know what it would take to get P&G back on track.”

Lafley went on to become a highly regarded and highly successful chief executive.

Amid a storm like that over Tylenol, Perry’s virtual silence prompts us to consider four questions we would ask about giving the CEO a leading role in responding publicly to a crisis.

1. When to bring out the CEO? The chief executive shouldn’t respond to every problem. There are several factors to consider before the CEO becomes the leading spokesperson, such as number of employees or customers affected, intensity of the media coverage, government scrutiny, or a decline in the stock price.

The Tylenol crisis checks most of those boxes. The overriding question is whether the crisis hurts the integrity of a company’s product or service; in Kenvue’s case, the safety of its customers.

2. When not to bring out the CEO? A CEO response can elevate a low-level crisis, intensifying the media coverage. That may explain why Perry has kept his head down.

If so, Kenvue may have underestimated the threat to the Tylenol brand, according to Steve Soltis, a lecturer at the University of Virginia Darden School of Business.

Perry and Kenvue’s board of directors may have been understandably worried about antagonizing a president willing to launch harsh attacks on those who oppose him.

But that challenge can be handled, Soltis told the school’s news site in an article published the day after the Sept. 22 news conference.

“You don’t want to get into a tit-for-tat with the President of the United States, regardless of who he or she is or what party they represent,” Soltis said. “Keep a respectful tone but also be emphatic in your convictions and track record. In the case of Tylenol, they have a long-standing track record of providing safe pain relief to billions of people on billions of occasions. They need to lean into that and the efficacy of their product.”

Indeed, Kenvue strengthened its statements defending Tylenol as the controversy continued.

3. Why pick the CEO? The answer is simple. “Depending upon the crisis, the response is more effective when the CEO is visible, caring, and engaged,” Geri Denterlein, CEO of Boston-based Denterlein wrote for Chief Executive in 2018. “Personal investment by the most powerful individual in the company sends a strong signal to employees, customers, and shareholders.”

4. Is the CEO up to it? We’ve seen chief executives stumble, fumble and bumble their way through a crisis response.

“In theory, the CEO is expected to be the voice of reassurance and trust amid crisis,” Chris Gidez, founder of G7 Reputation Advisory, told PRWeek in 2010. “But a crisis is not the time to test whether the CEO is up to the task. Advance preparation is critical.”

Perry, 59, would seemingly be a persuasive spokesman. He has experienced medical worries, and he’s comfortable talking publicly about a difficult topic, the role of religion in his life. When his daughter was 6 years old, she had kidney cancer and emergency colon surgery and recovered.

“He realized God wasn’t making his daughter suffer, but God was with them when bad things happened,” the Journal reported.

A veteran marketer, he took the Kenvue job after retiring late last year from a market research firm. In retirement, he hoped to coach high-school football, hunt elk and do missionary work with his wife.

He’ll get a chance to return to those activities soon. Kimberly-Clark, the maker of Kleenex and Huggies diapers, on Nov. 3 agreed to acquire Kenvue in a $48.7 billion transaction. Kimberly-Clark’s Chairman and CEO will lead the combined company.

Lessons from Lafley

Perry began his career in 1990 with P&G, working his way up before leaving in 2013. He likely picked up a few lessons from Lafley, who was P&G’s chairman and CEO from 2000 to 2010 and from 2013 to 2015, continuing as chairman in 2016.

In his 2009 article, Lafley said the chief executive’s unique role is to focus on the “Outside” of the organization and link the “Inside” to it.

He wrote: “The CEO alone experiences the meaningful outside at an enterprise level and is responsible for understanding it, interpreting it, advocating for it, and presenting it so that the company can respond in a way that enables sustainable sales, profit, and total shareholder return growth.”

That’s especially true in a crisis.

Tom Corfman, a senior consultant with Ragan Consulting Group, is a fan of the late management consultant Peter Drucker, who influenced A.G. Lafley.

Need help creating or updating your crisis plan? Email Tom to set up call with him and Nick Lanyi, an affiliate consultant with RCG and an expert in crisis communications planning.

Follow RCG on LinkedIn and subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.