How to Write Stories Frank Bruni Would Love

The New York Times opinion writer offers examples from a wide range of sources that demonstrate five basic writing techniques

In The New York Times Style Magazine last month, the newspaper’s chief restaurant critic wrote a story about the wide-ranging importance of eggs in culture, including baking.

“The whites alone, whipped steadily, foam up into a paralyzed surf and, when folded into batter — carefully, with as little effort as possible — bring a cake near levitation,” Ligaya Mishan wrote. “Gravity ends here. This is how angels eat.”

Why do these sentences work? There’s the structure: a series of short steps, like a recipe, separated by punctuation marks. The longest step is just seven words long.

There are the water images of foam and surf. Although when the waves of whipped eggs crest, they hold their shape. Then, when Mishan turns to the batter, the description shifts to floating. Then there’s the last sentence: a witty reference to a dessert known for its egg content.

Reading writing like this is one way to learn to write better.

Frank’s favorites

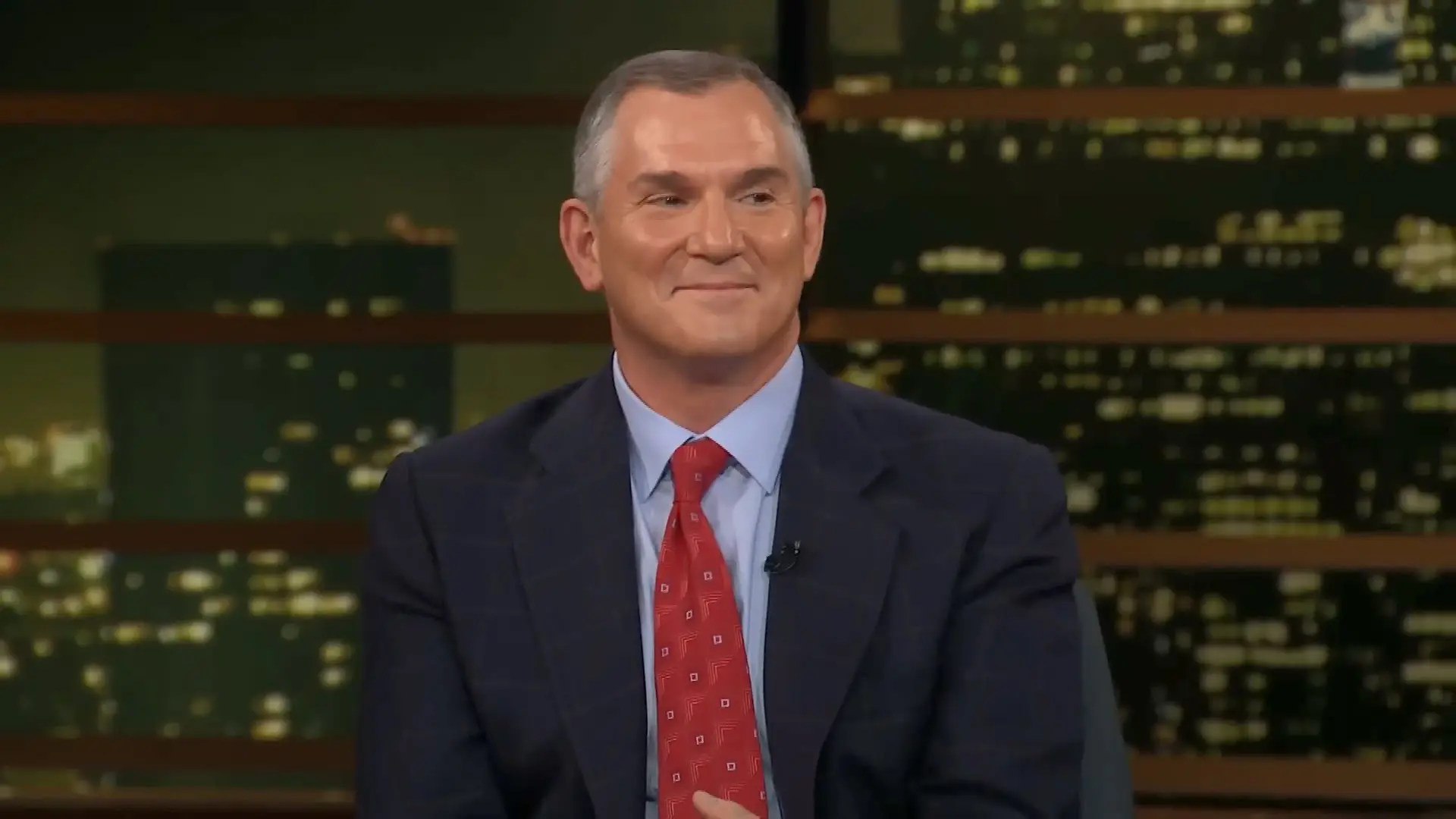

We would have missed this delicious writing example but for Frank Bruni, a former Times columnist who now writes a weekly newsletter for the newspaper, which is behind a paywall. Every month or so, he tacks onto the end of the newsletter “For the Love of Sentences,” reader-submitted examples from a wide range of publications.

Bruni, himself a former Times restaurant critic, included Mishan’s piece in the August newsletter. The newsletters are also published on the Times’ website.

Bruni, 60, covered several beats including the White House before being named the newspaper’s first openly gay opinion columnist in 2011.

Many of the writing examples are drawn from stories about government and politics, favorite topics for his newsletter and column, which ran until 2021, when he joined the University of North Carolina.

Bruni includes the examples without comment on why they’re so good. Some of the selections are brilliant flashes of creativity that can’t be taught.

But writing is also a craft. We identified five techniques from “For the Love of Sentences” that anyone can learn with practice. These techniques are a checklist to use as you read your first draft. Ask yourself: Do I have an ending? Are there words that sound alike that I can use? You’ll eventually write sentences that Frank Bruni would love.

1. Twist a cliché. Overused phrases are boring, but tweaking a cliché sparks interest.

For example, Bruni in January highlighted a story by Lookout Santa Cruz, an internet news outlet south of San Francisco, about the local impact of the nationwide egg shortage.

“We don’t know if the chicken came before the egg, but the avian flu definitely came before the egg shortage,” a reporter wrote.

Or consider this example from the July newsletter. A movie review in the Times had this line about the pandemic, “By late May 2020, even the most unflappable among us felt one raisin short of a fruitcake.”

David A. Graham, a staff writer for “The Atlantic,” responded in August to some liberals’ desire to find their own version of Donald Trump, Joe Rogan or Stephen Miller. He ended his piece this way: “For Democrats, imitation is the sincerest forum for getting flattened.”

2. Rhyme fest. Rhyme is a way to enliven your writing. In the May newsletter, Bruni highlighted a review in The Wall Street Journal of “Mission Impossible — The Final Reckoning,” starring Tom Cruise.

“Too often, the self-serving mission of making Mr. Cruise look cool clashes with the audience-serving mission of making sense,” Kyle Smith wrote. “The balance between vanity and sanity leans the wrong way.”

Smith sets up the rhyme with the first sentence, by repeating “serving mission.” But he changes the object from “self” to “audience.” (I’ll leave it to the rhetoric police to decide if the repetition is anaphora, epistrophe or symploce.)

Most people are unlikely to write in rhyme unless they are rappers like Che “Rhymefest” Smith, elected last year to the Chicago Board of Education.

But a rhyme might come to you as you read your first draft.

3. Details, details. A lot of great writing isn’t the result of a brilliant turn of a phrase. It’s the result of solid reporting: asking a lot of questions to find those details that sum up the story.

In the March newsletter, Bruni highlighted a Times story about the growing number of retailers selling firearm accessories. This is the first sentence: “Christmas was a few days away and Solomon Lehnerd was selling more grenade launchers than usual.”

Author David Litt described how he is different from his brother-in-law in this this essay, also highlighted in Bruni’s July newsletter. “It was immediately clear we had nothing in common. He lifted weights to death metal; I jogged to Sondheim.”

Since Litt is describing his brother-in-law, his eye for detail may be more of a factor than his reporting ability to get the detail. The key is to give readers relevant details, however obtained.

4. Soundalikes. Words that sound the same but have different meanings can add a little spice to a story.

In the June newsletter, Bruni highlighted a story in the Journal about the NBA championship series between the Oklahoma City Thunder and the Indiana Pacers. Pacers star Tyrese Haliburton badly injured his lower leg before the decisive seventh game.

“With apologies to the dairy industry, this is the most important calf in the heartland,” Jason Gay wrote.

The use of another kind of soundalike caught Bruni’s eye in a January newsletter. The sentence was in a movie review in the San Francisco Chronicle of “Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl,” an animated feature using the Claymation technique.

The writer ended the review by calling the movie “an impressive feat of clay, a winning choice in a competitive animated holiday season.” (This is also an example of tweaking a cliché.)

You don’t need to know that “calf” is an example of a homonym, a word that is spelled the same despite having different meanings. Or that “feat” and feet” are homophones, words that sound alike but have different spellings and meanings.

But as you’re rereading your copy, you should look for the opportunity to use soundalikes.

5. End with a bang. Communicators focus hard on how stories start. That’s important, but we often overlook how stories end, which can leave a lasting impression.

Endings are an opportunity to make the point of the first sentence but in a different way. Good examples are Graham’s piece on Democrats or the Wallace & Gromit review.

The first and last words of a sentence are the most important parts of a sentence, as writing coach Roy Peter Clark has taught. But that structural principle also applies to paragraphs, as the Times’ Mishan showed with, “This is how angels eat.”

In the June newsletter, Bruni highlighted the third paragraph of the Times’ obituary of Fred Smith, the founder of a well-known delivery company.

“FedEx was conceived in a paper that Mr. Smith wrote as a Yale University undergraduate in 1965. He argued that an increasingly automated economy would depend on fast and dependable door-to-door shipping of small packages containing computer parts. He got a grade of C.”

A strong finishing sentence is an integral part of a nut graph, the paragraph near the top of the story that sums it up.

Why care?

Bruni reflected on his experience as a teacher while expressing his concern about programs such as ChatGPT.

“I’ve lost count of the times when I’ve praised a paragraph, sentence or turn of phrase in a student’s paper and that student subsequently let me know that the passage had in fact been a great source of pride, delivering a jolt of excitement upon its creation,” he wrote in December. “We shouldn’t devalue that feeling. We should encourage — and teach — more people to experience it.”

Writing is craft, but the more you learn the craft, the more fun it becomes.

Tom Corfman was the editor of his fifth-grade newspaper, a mimeographed monthly called, “The Informing Five.”

Tom is a senior consultant with Ragan Consulting Group, where he directs the Build Better Writers program. Want to learn more about how we can help elevate the writing skills of your communication team? Email Tom to schedule a free, 30-minute conversation.

Follow RCG on LinkedIn and subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.