Writing + Editing = What?

A new book highlights how the two activities are one in the same

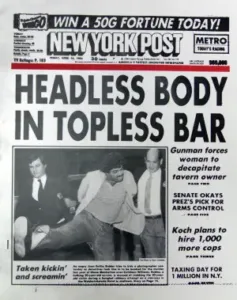

An editor almost killed the most famous headline ever written: “Headless body in Topless Bar.”

Vinnie Musetto, who was in charge of the New York Post’s front page in April 1983, settled on the headline soon after the story came in.

But as the New York Post raced to deadline, a night city editor held things up, saying, “We’re not a hundred per cent sure it’s a topless bar!”

That editor’s question met with some resistance in the newsroom but set off frantic fact-checking. With just minutes to spare, the key fact was verified, ensuring that the headline didn’t become a famous flop.

A new book reminded me of the story behind Musetto’s headline. “Editing: The essential guide to better writing across today’s media,” was published in August by academic press Cognella.

“Editing is needed now more than ever,” the authors write.

Newsrooms across the country are paying less and less attention to editing, the result of budget cutbacks amid declining revenues. Meanwhile, corporate communicators often take editing for granted, seeing it merely as rewriting. It’s much more.

The book has plenty for PR pros and internal communicators even though its primary audience is journalism students and professional journalists. Many of its tips and techniques we use in our Build Better Writers program.

That’s not a coincidence. The principles of good writing and editing are well-established. The trick is applying them.

What is a coincidence is that the authors, Buck Ryan and Michael O’Donnell, are former members of the faculty of the Northwestern University’s Medill school of journalism. My colleague Jim Ylisela was on the faculty with them and co-director of the Medill News Service from 1988 to 2001.

Another happy accident. I graduated from Medill in 1991 and still have a dog-eared copy of “The Editor’s Toolbox,” a 144-page handout by Ryan and O’Donnell and a forerunner of the current effort.

The 450-page book is a broad and detailed guide to big-picture topics, such as story structure, as well as the intricate rules of grammar and punctuation. The authors offer hundreds (thousands?) of examples and exercises so readers can grab on to the book’s insights. Writers as well as editors would be well served by picking up a copy.

Out of the book’s many useful lessons for corporate communicators, we’ve plucked out four:

1. Where it starts. In the first chapter, the authors ask, “Writing + Editing = What?”

“Writing!” is the answer.

“At that glorious moment when you’ve finished writing, take a breath and

realize that you’ve only just begun,” Ryan and O’Donnell write. “Step away and take whatever time you need to clear your mind. Then dive back in and begin editing.”

Being your own editor is hard, which is why we developed a 12-point self-editing checklist to help writers get started.

2. What’s newsworthy? Public relations people often peddle press releases without any news value, then are frustrated when reporters ignore them. Internal communications teams post stories on their intranets that bury the news, if there is any.

The authors include a 17-page summary of “the nature of news,” a needed antidote to the lack of understanding of these fundamentals.

We urge comms teams to set up their operations like their counterparts in the news media: First, assess your content and create an editorial structure. Second, create editorial guidelines and hold news meetings. A story memo or story pitch makes sure everyone is on the same page before serious reporting starts.

3. Sweeping up. Editing should be done in three sweeps, Ryan and O’Donnell write, each time focusing on “different levels of mistakes: killer, embarrassing and tedious.”

“You can’t think big and small at the same time,” they add.

Reading the copy all the way through while resisting the impulse to change anything is the key first step, we’ve said.

The authors note that some editors read sentences backward to avoid gliding over mistakes. That might be easy with sentences like the palindromic title to David McCullough’s 1971 book, “A Man, a Plan, A Canal, Panama!” later turned into a documentary.

We prefer reading the story out loud.

4. What’s ahead? Headlines often bedevil professional communicators, who tend to favor boring, keyword-heavy titles.

“In today’s world, where social media sites are a primary path to news and social interaction, knowing how to write short, punchy titles and headlines is more important than ever,” the authors write.

The authors outline three approaches to writing heds, as they’re called in newsrooms: skeleton, condense and patch, and seed methods. These techniques make clear what veteran headline writers do instinctively.

A hed should help “move the reader one step at a time through the story, we wrote recently. Simple headlines are more engaging than complex ones.

We’ve highlighted just a few of the book’s lessons, which include structuring sentences, editing quotes, constructing ledes (or first sentences) and trimming stories. That’s not to mention a 127-page appendix, a useful reference on grammar, punctuation and spelling.

The book’s clarity is a testament to the authors’ experience as teachers. Ryan is now a professor at the University of Kentucky in Lexington, while O’Donnell is professor emeritus at the University of St. Thomas in Saint Paul, Minn.

Meanwhile, Musetto went from being a Page One editor to a film critic for the Post. He died in 2015.

The “headless” headline wasn’t his favorite. That honor went to a 1984 story about a convicted serial killer who wanted to be put to death in her night clothes.

The headline? “Granny Executed in her Pink Pajamas.”

Headlines and ledes are a bit of an obsession for Tom Corfman, a senior consultant with Ragan Consulting Group who directs our Build Better Writers program.

Contact our client team to learn more about how we can help you with your communications. Follow RCG on LinkedIn and subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.