Communications at GM’s Cruise: Not Just the Cars were Driverless

A new report on the October accident in San Francisco furnishes four lessons on crisis communications.

What’s it like to read the independent report released late last month on how Cruise’s top executives handled a San Francisco accident in which one of its driverless cars struck and hit a pedestrian?

It’s like watching a horror movie in which teenagers are trapped in a big rambling house with the power out and a slasher on the loose. Many passages in the 195-page report make you want to scream: Don’t do that! Don’t open that door! Don’t say that!

But time and again, the leaders of the General Motors subsidiary did exactly what they shouldn’t when responding to the October accident in San Francisco, where the company had been operating driverless taxis since early 2022.

Cruise did not candidly disclose to regulators that the car dragged the woman about 20 feet after hitting her, Los Angeles-based law firm Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan found. But company executives didn’t intend to deceive. Instead, the firm blamed a “failure of leadership” and an “us-versus-them” mentality.

The woman was seriously injured in the Oct. 2, 2023, accident and taken to a hospital. She was discharged in January.

The consequences to the company have been dramatic. Before the month was over Cruise pulled its cars from the streets nationwide after California regulators found they posed a danger to the public. Nearly a quarter of its employees have been laid off and the U.S. Justice Department and other governmental agencies are investigating.

Among the cavalcade of errors by Cruise executives, one will stand out to professional crisis communicators: They didn’t believe they had an obligation to tell the news media that their version of events was wrong.

“Reporters are reporting what we said and not disputing the facts,” Aaron McLear, the vice president of communications and analytics, said in an internal message. He’s one of 11 senior executives, including the CEO, who no longer works for Cruise.

The law firm’s report, released by Cruise on Jan. 25, 2024, offers a minute-by-minute and day-by-day view into a major company’s response to the worst accident in its history. It also provides corporate communications with four lessons on the proper response to a big crisis.

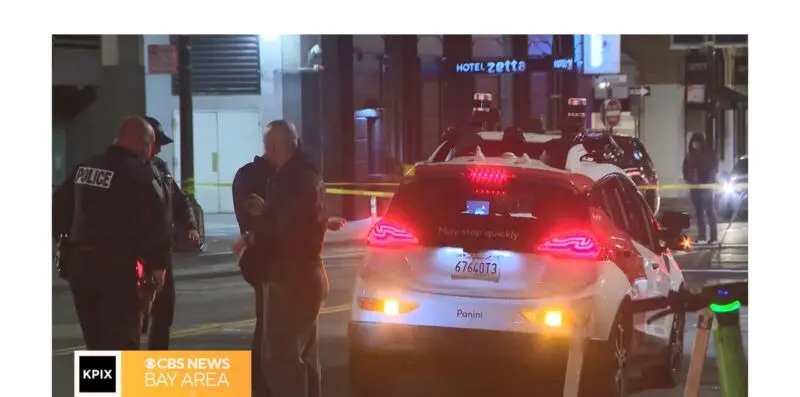

The accident

At about 9:29 p.m. on Oct. 2, the driver of a Nissan Sentra hit a pedestrian near Union Square, pushing her into the path of the oncoming Cruise car, which then hit her. The driver of the Nissan fled the scene. The accident was recorded by cameras on the Cruise car. When the San Francisco Fire Department arrived about four minutes later, it found the woman pinned under the Cruise car.

First media reports

The Fire Department initially reported that the Cruise car had caused the accident, which fueled incorrect media reports. The Cruise car was equipped with nine video cameras.

Within minutes, the executives learned the reports were wrong after seeing preliminary videos that stopped after the driverless car hit the pedestrian. Executives became obsessed by the coverage.

“We are under siege,” Prashanthi Raman, vice president of global affairs said to a colleague shortly before midnight. “We are drowning.”

Immediately, “Cruise leadership was fixated on correcting the inaccurate media narrative,” Quinn Emanuel found. This “myopic focus” led executives “to omit other important information about the accident,” the firm said.

Lesson #1 Keep your cool. It’s easy to feel defensive, much harder to be objective.

The public statement

The company quickly decided to show reporters a video that stopped before the Cruise car hit the pedestrian.

On Oct. 3, 12:53 a.m., the company issued a statement on the social media site X blaming the Nissan driver. It was heavily edited by the CEO, Kyle Vogt, and McLear. The statement does not mention that the pedestrian was dragged because the execs were not aware of that fact.

Instead, the statement says the Cruise car “braked aggressively to minimize the impact.”

The law firm doesn’t address what senior executives should have known, but within an hour of the accident a company contractor on the scene saw blood and skin patches on the ground, revealing that the pedestrian had been dragged by the Cruise. That information did not reach senior executives.

Under such circumstances, Cruise cars were programmed to execute a “pullover maneuver,” moving as much as 100 feet to get to the side of the road.

Lesson #2 Know what you don’t know. When Cruise issued its statement, there was important, unreviewed evidence that could have, and ultimately did, contradict the claim that the Cruise car “minimized” the impact. An awareness of what you don’t know may prompt you to be more conservative in your initial message to avoid misstating or underplaying the facts.

The next morning

A 45-second video, posted internally in the middle of night, showed the Cruise car braking but also hitting the pedestrian and then dragging her under the car. At a 6:45 a.m. meeting, Vogt, McLear and other senior executives discussed amending the public statement.

“The outcome was whatever statement was published on social we would stick with because the decision was, we would lose credibility by editing a previously agreed upon statement,” one person told the law firm.

As McLear explained in an internal message, “We did share all the info with all of our regulators and the investigators. We have no obligation to share anything with the press.”

Of course, Quinn Emanuel found the first sentence wasn’t true either.

Lesson #3 If you make a mistake, fix it. In a rapidly changing situation, where new information is coming in, mistakes will happen. Your credibility will be more damaged by concealing a misstatement than by acknowledging a good-faith mistake and explaining why it happened.

Getting out in front of this mistake would have avoided the next lesson.

The Forbes reporter

On Oct. 5, a reporter for Forbes magazine told Cruise’s comms team that the president of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors said the company knew that the driverless car had dragged the pedestrian but wasn’t disclosing it. He asked to see the 45-second video.

Company executives considered admitting what it knew, but instead opted to stand by its earlier statement, fearful of triggering a new media cycle. The article, published Oct. 6, was the first public report about the dragging. The story intensified regulators’ scrutiny,

Lesson #4 Tell the truth. Standing by an earlier statement the company knows to be false was tantamount to lying, which is the worst mistake you can make in media relations.

Ordinarily, you wouldn’t look to a big law firm for public relations advice, but we’ll give Quinn Emanuel the last word:

Cruise leadership failed to appreciate that by disseminating partial information about the accident well after they were aware of the pullover maneuver and pedestrian dragging, Cruise allowed the media to believe that the only information of any public import was that the Nissan, not the Cruise AV, caused the collision. This was untrue and inappropriate, and has triggered legitimate criticisms from media outlets that Cruise misled them about the full details of the Accident.

Not bad for a bunch of lawyers.

Tom Corfman is a lawyer and a senior consultant at Ragan Consulting Group, where he trains communicators to raise red flags when their bosses take a wrong turn. In addition to being part of the crisis communications team, he also leads the Build Better Writers program.

Contact our client team to learn more about how we can help you with your communications. Follow RCG on LinkedIn and subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.