What’s a PR Person to Do if There’s No Objectivity in Journalism?

5 tips for dealing with a reporter pushing a point of view.

Edward R. Murrow once said, “To be persuasive we must be believable; to be believable we must be credible; to be credible we must be truthful. It is as simple as that.”

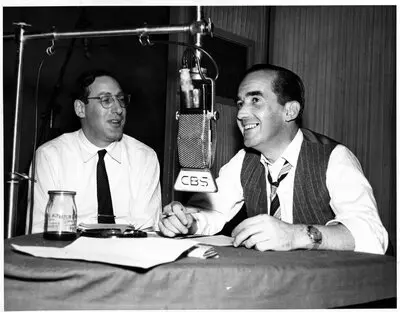

That sounds like the father of broadcast journalism, who is still remembered for his brave reporting on the red scare tactics of U.S. Sen. Joe McCarthy. But he didn’t say it during his long career with CBS News.

Instead, he made the statement while testifying before Congress in 1963, two years after he became director of the U.S. Information Agency, the parent of Voice of America. Despite the propaganda mission of the agency, Murrow tried to set a different direction.

Of course, it wasn’t as simple as that, as Murrow tried to balance truth with the objectives of USIA amid his agency’s deepening ties with the Central Intelligence Agency. That makes his quote even more valuable today to public relations people wrestling with increasingly skeptical and opinionated reporters.

What’s sometimes called “objective” journalism is being replaced with what I’d call “point of view” journalism, although there’s no formal definition. To better connect with their audiences, journalists are more likely to state conclusions, explaining what a story means and why it’s important, as we’ve explained. There’s more focus on storytelling.

Reporters don’t root for one side or another. They root for the story, or whatever they think will make a better story. Taking advantage of that journalistic desire is a way public relations people can shape point-of-view stories. You may not change any minds, but you can influence the outcome. Here are five tips:

1. Build relationships. Public relations has become highly structured: Issue a press release, take questions by email, respond by email after a series of approvals that take up time reporters feel they don’t have. There’s a reason for this. Everyone’s afraid the reporter is going to make them look bad!

The way to break through that fear is to get to know the reporters who cover your organization. Study them like sales prospects, connect with them in no-pressure situations. Give them a compliment.

John Darnton, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter and editor with The New York Times, once wrote, If you ever want to reach reporters with a compliment, don’t tell them they dug out all the facts or presented them fairly. Tell them they write “brilliantly.”

2. Give reporters something more. A recent article in The New Yorker describes the historic dance between the press corps and government officials that offers insights into the relationship between reporters and the companies they cover.

If reporters feel they need access to company information to prepare their stories, there’ll be pressure to remain on good terms with their sources. But the pressure’s off if all reporters get the same news releases and no reporter is rewarded with answers to smart, if tough, follow-up questions.

To curry favor with reporters, keep the information flowing.

Some organizations don’t give exclusives to reporters, and there’s something to be said for not playing favorites (or not being caught doing so). But there’s also a newsroom saying, “If you give news to everybody, it isn’t worth anything to anybody.”

3. Find the hero. Every story needs a central character, whether it’s a maintenance worker who stops up the broken pipe flooding a data center or a CEO with a turn-around plan. Reporters look for one person to tell a story through, personalizing the news.

Finding and describing that central character for a reporter will help determine whether a story is favorable or unfavorable to a company. Is the story about an employee who saved a day or someone else? (To be sure, the choice is seldom that stark.) Is the hero a true character? Well qualified? With a compelling background?

In addition to identifying a protagonist, pay close attention to other elements of narrative, such as color, emotion and movement.

4. Find the challenge. Risks and challenges are what audiences find compelling and why many journalists are attracted to business reporting.

Like Odysseus or Luke Skywalker, chief executives are heroes who must overcome challenges more real than the cyclops or Darth Vader. A key element in business reporting today is finding that point of tension in a story.

“Reporters are biased toward conflict because it is more interesting than stories without conflict,” the deputy editor of Columbia Journalism Review wrote in 2003.

The company’s challenges are already laid out in SEC filings, analysts’ reports and earnings calls or by competitors. Help reporters find them and how the CEO proposes to triumph over them.

5. Ask about the point of view. PR people tend to assume the personality of the people they represent. Be like U.S. Sen. Charles Schumer’s people: Dig into the details.

“Being transparent about point of view is the honest approach for reporters,” according to an article by Jay Rosen, a journalism professor at New York University.

Many reporters will say they don’t believe in objectivity. If so, fair is fair.

Ask reporters about their take on a story. What facts are they going to use? Freely participate in fact-checking. Some reporters may object, hiding behind the cloak of objectivity. It’s easier to get answers if you and the reporters know each other.

Recent questions about objectivity in journalism are hardly new. Murrow included conclusions in some of his reports. His critics said he was substituting his opinion for facts. McCarthy accused him of being a communist. His bosses and sponsors hated the controversy.

In a biography published in 1989, historian Joseph Persico wrote, “For all his professed journalistic objectivity, Murrow was a subjective reporter, and it was this very subjectivity that lent his reporting its heart and its fire.”

Today, we’d say he was establishing a point of view, supported by facts.

Murrow died in 1965. The title of a 2005 movie about the broadcaster and his clash with McCarthy was also Murrow’s long-time signoff, which is as good advice as any: “Good night, and good luck.”

This is the second of two stories about objectivity in business journalism. The first story is here.

Tom Corfman is a senior consultant with Ragan Consulting Group, where he coaches organizations on how to deal with those rascally rabbits, er, reporters.

Contact our client team to learn more about how we can help you with your communications. Follow RCG on LinkedIn and subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.