9 Tips on How to Coach Writers

Talking about a story before a word is written saves time and creates better stories.

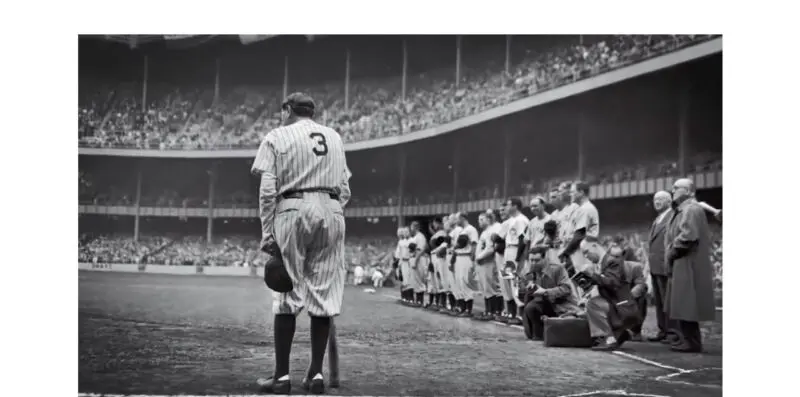

Nat Fein shot a photo of Babe Ruth during the slugger’s final appearance at Yankee Stadium that won the New York Herald Tribune photographer a Pulitzer Prize. More than 75 years later it’s an example of the value of coaching.

The story behind that photo is cited in “Coaching Writers: The Essential Guide for Editors and Reporters,” by Roy Peter Clark, a senior scholar at The Poynter Institute, and Don Fry, who was an associate at the St. Petersburg, Florida journalism training center.

“Coaching involves nothing more than talking with writers, in certain ways,” they wrote more than 30 years ago. The “certain ways” are intended to help writers create stories that are well reported, more sharply focused and better organized.

Many corporate communication managers and leaders feel hard-pressed to make time to talk to writers. Yet taking that time before a story is filed will increase a writer’s pride in authorship and save the manager time rewriting the story later.

Before we turn to tips on coaching writers, let’s look at the backstory of the photo known as “Babe Bows Out.”

The Babe’s Day

The ceremony on June 13, 1948, marked the 25th anniversary of “The House that Ruth Built” and the retirement of the slugger’s No. 3 jersey. Two months later, Ruth, 53, died of cancer.

That day, Fein was filling in for a sports photog who called in sick. The Manhattan native’s specialty was human-interest photos.

On an overcast day, when other photographers were using flash, Fein didn’t. And he took a photo of Ruth’s back, defying the convention of shooting his front. Why?

Fein, who died in 2000, recalled talking to his picture editor before going to the stadium for the historic day.

“The boss told me to go up to Yankee Stadium because that was the day Babe Ruth was retiring and this would be one of the last times to get a shot of the Babe’s No. 3,’’ Fein recalled in a 1986 interview.

In those days, the numbers were not on the front of the uniform.

“He drilled into me to get that No. 3, so that’s what I did,” Fein said. “I took a lot of shots, but there was that one from the back with that No. 3 over those spindly legs.”

The editor also suggested, “Whenever you can, make your pictures without flashbulbs. Natural light catches the mood of the occasion.”

It was the coaching that led to an award-winning photograph. But in a corporate comms department, your managers and leaders may feel uncertain about how to advise their writers. Even if they’ve worked as journalists, coaching isn’t practiced in many newsrooms.

That’s where “Coaching Writers” comes in. While thinking about how to help writers, I stumbled upon the book, published in 1992. (In writing this story, I used the hardcover first edition, which is available for a reasonable price. A second edition, published in 2003 as a college textbook, promises to include tips on coaching for digital channels.)

The book offers specific suggestions on how to talk to writers about their stories, which inspired me to add some of my own.

Here are nine tips:

1. Brainstorming. If the comms team doesn’t want to be order takers, they must find newsworthy stories about their organization. To train writers to think that way, have a conversation once a week that starts with, “What do you hear that’s going on?”

Clark and Fry suggest questions such as:

- “Which of these ideas really turns you on?”

- “Can you think of a way to do that story that hasn’t been tried before?”

Some ideas will fall to the bottom. That’s OK. Scoop up the ideas that float to the top.

2. The memo. Before writers start work, we recommend they write a story or pitch memo. But before they do, have a conversation. Donald Murray, who was a Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial writer and writing coach for several newspapers, offers this advice in the book: “Ask the writer to suggest ways of reporting and writing the story. If your idea turns out to be the writer’s idea, then you’re ahead of the game. If the writer’s idea is better, you’re way ahead.”

3. The start. Once the story gets a green light, should there be another chat? If the story was approved at a news meeting, were there any questions or suggestions? Do you have additional thoughts? Reassure the writer it will all get done, and expertly.

4. Constant updates. There was a reporter-turned-editor at Crain’s Chicago Business who used to say, “Constant updates, that’s the key.”

Ask writers questions about the progress of the reporting. Clark and Fry suggest:

- “How can I help you?”

- “How do you feel about the piece so far?”

We prefer brief, impromptu conversations instead of an exchange by email or a messaging app, but that choice depends on your company culture.

5. Repeat, repeat, repeat. “Ask the most important questions over and over again,” according to Clark and Fry, who died in 2021.

Among their suggestions:

- “What does the reader need to know?”

- “What’s this story about?”

- “What’s your best quote?”

I’ll add one more: “Why should we care about this story?”

With your voice in their heads, your reporters will begin asking themselves these questions while they’re reporting and editing.

6. The big interview. In every story there’s usually one or two key interviews. That’s when reporters are usually excited and want to talk. That’s time to circle back. As reporters go through their interview with you, help them organize their thoughts.

7. Follow the news. As a writer recaps their reporting, be alert to things that make the story bigger or different than expected. These are sometime offhand mentions: “Oh, and she said …”

Part of an editor’s job is to see the bigger picture. We love story memos, but it’s a marriage of convenience. Toss it out if the story changes.

8. “What happened?” Helping a writer who’s lost in a story can be simple as asking that question.

The chronology is the writer’s friend. The story may not be told that way, but you must master it before you decide: Start in the middle or start at the end, then jump to the beginning.

Once reporters walk through a story from beginning to end, they’ll find their way.

9. Ask, then edit. After the story is filed, ask the writer to appraise the piece: What worked? What needs help? What needs more reporting? What would you do differently?

Many times, a writer struggles with a problem and doesn’t quite get it right. That’s the one an editor usually spots and must try to fix. Asking creates a shared goal for the editing.

Fein, who died in 2000 at age 86, admitted that when he took the Ruth photo, he was uncertain what he had.

“I didn’t think it was a great shot,” he said.

Good thing he had an editor to talk to.

Tom Corfman is a senior consultant with Ragan Consulting Group, where he leads the Build Better Writers program. He loves listening to reporters talk about their stories.

Contact our client team to learn more about how we can help you with your communications. Follow RCG on LinkedIn and subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.